“We have a list of officers . . .”: The Fight For NYC District Attorneys’ Police Adverse Credibility Lists

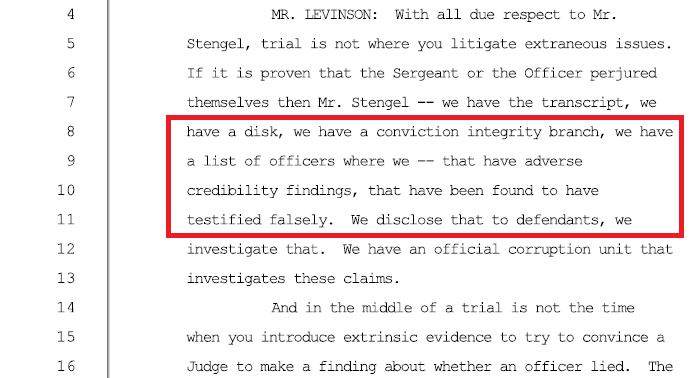

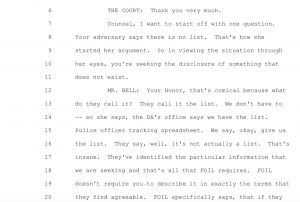

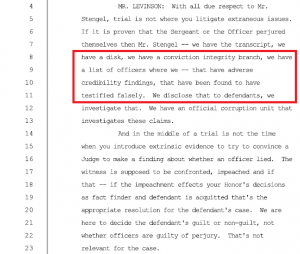

“We have a list of officers . . . that have adverse credibility findings,” a Manhattan District Attorney deputy bureau chief disclosed.

“We have a list of officers . . . that have adverse credibility findings.” That’s what a deputy bureau chief in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office disclosed in open court in early 2017. He was talking about a list of police adverse credibility, or lack thereof, and in particular, members of the New York City Police Department or NYPD.

That public admission, nearly two and half years ago is what led to the Bronx District Attorney to disclosure their list of police officers with adverse credibility findings to two reporters and me, hyperlinked at the bottom of this post. Now, the Manhattan District Attorney may be on the verge of disclosing the version of the list.

The other New York City District Attorneys, Queens, Staten Island and presumably Brooklyn, claim that they have no such list. Even the Bronx District Attorney’s Office denied that it had a list of NYPD adverse credibility findings 15 months ago. But first the backstory.

In February 2017, I represented a client who was falsely arrested and charged with a sex crime in Manhattan. The arrest was based on the alleged observations of three members of a plain clothes NYPD anti-crime team—but by any complaining witness.

My client had secretly recorded the police officers talking openly immediately after his their arrest. The audio recording made plain that the police were lying about the circumstances of his arrest and, more specifically, that they had tried to induce a potential complaining witness to claim that a different crime had occurred, but she refused. Following his arrest, my client was transported to the police precinct by uniformed police officers, while his belongings and the anti-crime team went to the precinct in a separate vehicle, which made the recording and the shocking candid admission possible.

Due to an odd set of circumstances, the second of two anti-crime police officers who was scheduled to testify became my witness instead of a witness for the prosecution. So, the deputy bureau chief argued against the admissibly of the recording. If you’re wondering why the case wasn’t dismissed outright when the devastating audio recording was disclosed, so was I. The Appeal chronicled the wrongheaded prosecution of my client with a story is headlined, “Two Cops Said They Saw A Man Grope Women. The Women Disagreed. The DA Charged Him Anyway.” That deputy bureau chief is now the head of legal training for the Manhattan District Attorney. That’s when the deputy bureau chief disclosed the existence of the list of police officers with adverse credibility. He said the list focused on police who testified falsely. We now know that the list is far broader than that.

The deputy bureau chief described a record maintained by a public agency, i.e., the Manhattan District Attorney, which falls under the New York’s Freedom of Information Law or FOIL. During our back and forth I made a mental note to send a FOIL request for the list. But first I was focused on winning a not guilty verdict. My client was found not guilty and a civil rights lawsuit is pending.

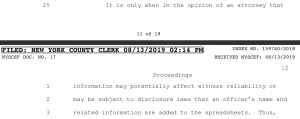

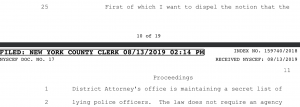

In March 2017, I sent a FOIL request for the list of adverse credibility finding to the Manhattan District Attorney. I am currently in Article 78 litigation with the Manhattan District Attorney to force the disclosure of the list. On July 18, 2019, during oral argument on the Article 78 petition, the lawyer representing the Manhattan District Attorney claimed that no such list of adverse credibility exists. The lawyer conceded that there is a spreadsheet that contains information regarding police officer adverse credibility, but don’t call it a list!

The absurd contradiction by the attorney arguing on behalf of the Manhattan DA was handled brilliantly by Henry Bell, Esq., who is representing me in the Article 78 petition for the list (or spreadsheet!).

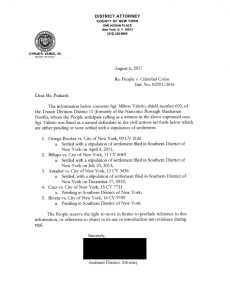

Disclosure of letters sent to defense attorney by the Manhattan District Attorney from 2015 to 2018 regarding police adverse credibility.

During the pendency of the Article 78 against the Manhattan District Attorney, I sent another FOIL request, this time for the fruits of the list, disclosures made to defendants based on the list of adverse credibility findings. In January 2019, the Manhattan District Attorney disclosed 23 such letters to me.

In October 2018, I sent a follow up FOIL request to the Manhattan District attorney for disclosures made to defendants based on the list since my last request. That request was denied for invalid reasons, including the pending Article 78.

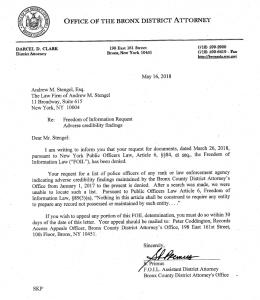

In May 2018, Bronx District Attorney denies that the office maintains a list of police officer adverse credibility.

I also sent FOIL requests to the other New York City District Attorney’s Offices: the Bronx, Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island all claimed that no such list exists in each of their offices (actually, I don’t recall receiving a reply from the Brooklyn District Attorney.)

In May 2018, the Bronx DA’s Office claimed that they were unable to locate a list of police officers with adverse credibility findings.

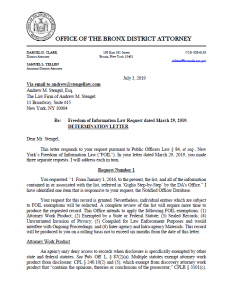

In July 2018, the Bronx District Attorney admits it maintains a list of police officers with adverse credibility.

Based on a hunch and I sent a second FOIL request to March 2019 for their list of police officers with adverse credibility findings. The second time was the charm. In May 2019, the Bronx District Attorney’s Office, contradicting their prior denial, acknowledged that they in fact had a list of police officers with adverse credibility findings.

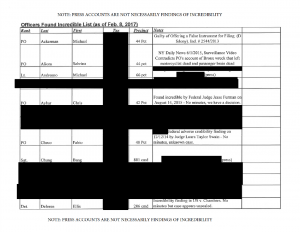

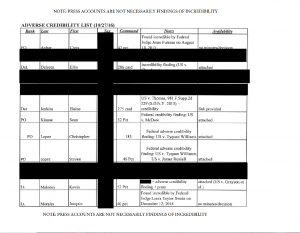

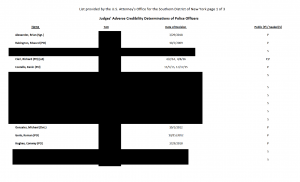

That brings us to present day. Last week, the Bronx District Attorney’s Office finally disclosed their list. They initially could not find one list, now–surprise!–they have three such lists. The PDF files of the lists are hyperlinked below via each of the images.

The first list is five pages and a collection of press accounts and lawsuits. It’s quaint file name is “Officers Found Incredible List.”

The second list, titled “Adverse Credibility List” is two pages and includes adverse credibility findings from federal judges.

The third list, “Judges Adverse Credibility Determinations of Police Officers,” is three pages. The list was apparently provided to the Bronx District Attorney by the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District.

District Attorneys’ disclosure of police officer adverse credibility to defendants during prosecution is typically untimely and often irregular. The adverse credibility of a police officer, if ever disclosed, is given to a defendant far down the road, sometimes on the even of a hearing or trial. Most cases are disposed of by a plea bargain. As we know well, defendants who aren’t in fact guilty do plead guilty in order to avail himself or herself of a favorable plea bargain. The Hon. Jed Rakoff, the esteemed retired Senior Justice of the Southern District of New York, covered the issued brilliantly in Why Innocent People Plead Guilty. An Oklahoma man recently pleaded guilty to cocaine possession and was sentenced to 15 years in prison, when the white powered was actually powdered milk. Why did he plead guilty? To get out of county jail.

Defendants routinely make decisions about whether or not to accept a plea bargain without knowing that a police officer has been found to have adverse credibility. That information would likely change the calculus about whether to risk a trial or to accept a plea bargain, especially when police are the only witnesses to an alleged crime.

During the oral argument for the Article 78, the attorney for the Manhattan District Attorney attempted to carve out a new exception from disclosure under FOIL. She claimed that “the public’s interest would not be served by FOIL access to subjective and potentially damaging non-public information or allegations about specific persons in the court of public opinion, where it would be subject to premature evaluation and exploitation.” That argument smacks against the very purpose of FOIL.

The legislative declaration when FOIL was enacted, Public Officers Law § 84 states, “The people’s right to know the process of governmental decision-making and to review the documents and statistics leading to determinations is basic to our society. Access to such information should not be thwarted by shrouding it with the cloak of secrecy or confidentiality. The legislature therefore declares that government is the public’s business and that the public, individually and collectively and represented by a free press, should have access to the records of government in accordance with the provisions of this article.” To put that in context here, the general public–and defendants facing prosecution–have a right to see records that show that a police officer protects and serves and lies.